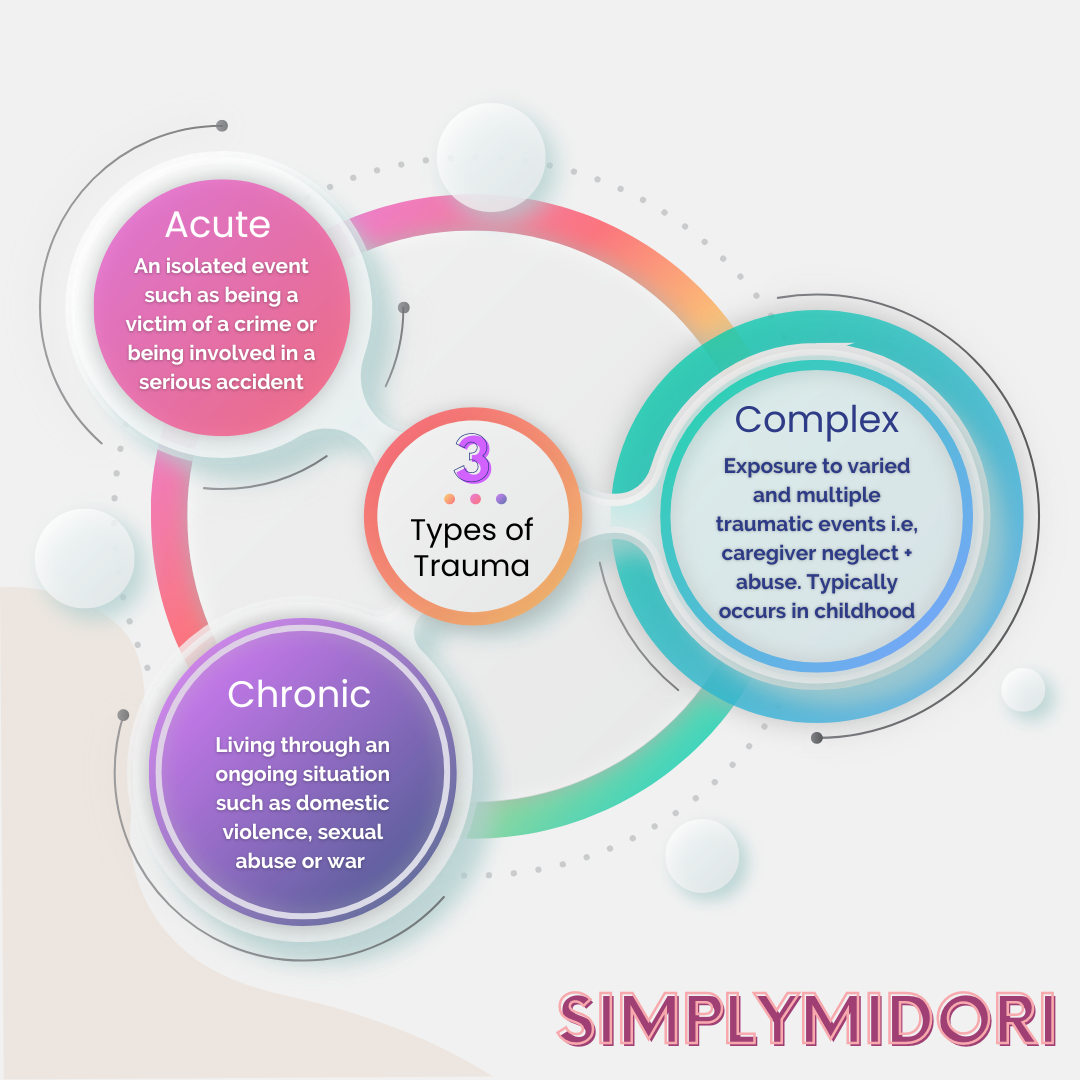

Trauma comes from the Greek word for wound or hurt. As of today, we now have three main types of trauma (complex trauma, chronic trauma, and acute trauma), along with a better understanding of how our mental health is impacted after trauma.

Explore the essence of trauma in this blog, unraveling its definition, dissecting the distinctions among the three types of trauma, and delving into the diverse triggers that instigate traumatic experiences.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) defines trauma as:

Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways: (1) Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s); (2) witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others; (3) learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend – in cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must have been violent or accidental; (4) experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (e.g., first responders collecting human remains; police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse) (Note: Criterion A4 does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures unless this exposure is work-related).

What Are Discrepancies With The DSM & Types of Trauma?

While this definition is helpful, some argue against the need for trauma to be restricted to “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence,” as many events can be traumatic even without a direct threat to life or injury (Briere, 2004; Anders, Frazier, & Frankfurt, 2011). Secondary trauma, also known as vicarious trauma or compassion fatigue, affects individuals who are exposed to the traumatic experiences of others, such as healthcare professionals and therapists.

The earlier DSM-III-R (APA, 1987) defined threats to psychological integrity as valid forms of trauma. Since the DSM-5 doesn’t classify events as traumatic unless they’re life-threatening, it likely underestimates the true extent of complex trauma in the general population by excluding highly upsetting experiences like extreme emotional abuse, major losses or separations, degradation or humiliation, and coerced (non-physically violent) sexual encounters.

It also limits the diagnosis of stress disorders in some people with significant posttraumatic distress because Criterion A is a requirement for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and acute stress disorder (ASD) diagnoses. Whether an event must meet current diagnostic criteria for trauma to be considered “traumatic” is an ongoing topic of discussion in the field.

What Is Trauma?

Trauma is an event that’s highly upsetting, overwhelming a person’s internal resources, leading to lasting psychological symptoms. Trauma symptoms can manifest emotionally, mentally, and physically, affecting the severity and duration of a person’s reaction to trauma.

We use this broader definition in our blog because individuals facing significant threats to psychological well-being can suffer as much as those traumatized by physical injury or life-threatening situations. We think they can also respond equally well to trauma-focused therapies. However, for formal stress disorder diagnoses, it’s important to adhere to the specified version of trauma.

What are the three main types of trauma?

Acute trauma

Acute trauma refers to a highly distressing event that occurs suddenly, causing intense emotional or psychological shock and overwhelming an individual’s ability to cope effectively. It often involves experiencing or witnessing a threat to one’s physical or mental well-being, such as a natural disaster, serious accident, violent assault, or sudden loss of a loved one.

What are the effects of Acute trauma?

Acute trauma can have profound and immediate effects on an individual’s emotional, psychological, and physical health. When someone experiences acute trauma, their body’s stress response system, including the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, goes into overdrive.

This heightened state of arousal can lead to mental health symptoms such as intense fear, anxiety, panic, confusion, dissociation, or numbness. In some cases, individuals may experience physical symptoms like rapid heartbeat, trembling, sweating, or difficulty breathing.

The psychological impact of acute trauma can vary depending on factors such as the nature of the event, the individual’s coping skills, their support system, and any past experiences of trauma. Some individuals may recover relatively quickly and resume their normal functioning.

In contrast, others may struggle to cope with the aftermath of acute trauma and develop acute stress disorder (ASD) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Acute trauma can also lead to the formation of traumatic memories, which may require therapeutic approaches like EMDR and trauma-informed therapy to address and process.

Chronic trauma

Chronic trauma refers to repeated or prolonged exposure to highly stressful or traumatic events over an extended period. Unlike acute trauma, which involves a single distressing event, chronic trauma involves ongoing and often cumulative experiences of trauma that can have pervasive and enduring effects on an individual’s well-being.

Chronic trauma can occur in various contexts, including ongoing physical or emotional abuse, neglect, domestic violence, community violence, war or conflict, systemic oppression, or living in unstable or unsafe environments. These experiences can lead to profound disruptions in an individual’s sense of safety, security, and trust in others.

What are the effects of Chronic trauma?

The effects of chronic trauma can be far-reaching and may impact multiple areas of a person’s life, including their physical health, mental health, relationships, and overall functioning. Chronic trauma can manifest in a wide range of symptoms, which may vary depending on factors such as the nature and severity of the trauma, the individual’s coping mechanisms, and their support system.

Common symptoms of chronic trauma may include:

- Persistent feelings of fear, anxiety, or hypervigilance

- Flashbacks or intrusive memories of traumatic events

- Avoidance of reminders of the trauma

- Difficulty regulating emotions or controlling impulses

- Negative beliefs or self-perceptions

- Challenges in forming and maintaining relationships

- Mental & physical health problems, such as chronic pain or somatic symptoms

- Substance abuse or other maladaptive coping behaviors

Living with chronic trauma can be incredibly challenging, and individuals may experience a range of coping strategies to manage their symptoms, including avoidance, dissociation, or numbing. However, these coping mechanisms may provide temporary relief but can ultimately exacerbate the long-term impact of trauma.

Complex trauma

Complex trauma, also known as complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD), refers to prolonged or repeated exposure to traumatic events, typically beginning in childhood and continuing into adulthood.

Unlike acute or chronic trauma, which involve discrete traumatic incidents or ongoing stressors, complex trauma encompasses a broader range of adverse experiences, such as abuse, neglect, interpersonal violence, or abandonment, occurring within the context of relationships and over an extended period.

What are the effects of Complex trauma?

Complex trauma can have profound and pervasive effects on an individual’s mental health development, sense of self, and interpersonal relationships. Individuals who have experienced complex trauma may struggle with emotional regulation including difficulty managing intense emotions like fear, anger, shame, or sadness, often resulting in frequent mood swings or outbursts.

This can lead to a fragmented self-concept, feelings of worthlessness, and struggles with self-esteem. These challenges can strain relationships, making it hard to form secure attachments and leading to interpersonal difficulties or social isolation.

Coping mechanisms such as substance abuse or self-harm may be used to numb painful emotions, while adaptive survival strategies like dissociation or hypervigilance may develop to cope with ongoing threats.

Additionally, complex trauma can have long-term physical health impacts, including chronic pain, gastrointestinal issues, and cardiovascular problems due to the physiological effects of stress on the body. Trauma-informed care is crucial in therapeutic settings to create a safe and validating environment for individuals to process traumatic experiences, develop coping strategies, and connect with support networks.

Related Reading: Learn How Trauma Controls Our Adult Relationship

Is It Normal For People To Experience Trauma?

Studies of the overall population show that over half of adults in the United States have gone through at least one significant trauma (Elliott, 1997; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995; Norris, 1992).

It is important to recognize trauma symptoms, which can manifest emotionally, mentally, and physically, and may indicate the need for support and treatment.

While traumatic stressors are widespread, their impact on causing significant psychological symptoms and disturbance depends on various factors. Below, we will outline the main types of traumatic events that individuals seeking mental health services may have experienced.

What Are The Different Causes and Symptoms of Trauma?

Trauma can stem from a wide array of events, each leaving a unique imprint on an individual’s psyche. Physical or emotional abuse, neglect, natural disasters, accidents, and witnessing violence are all potential sources of trauma. These traumatic events can overwhelm a person’s ability to cope, leading to lasting psychological effects.

The symptoms of trauma can vary widely depending on the individual and the nature of the traumatic event they experienced. Common symptoms include anxiety, depression, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and insomnia. Individuals may also experience physical symptoms such as headaches, stomachaches, or chronic pain. Emotional abuse, in particular, can lead to feelings of worthlessness, shame, and difficulty trusting others. Recognizing these symptoms is crucial for seeking appropriate help and support.

Child Abuse

Childhood sexual and physical abuse can vary from fondling to rape and from severe spankings to life-threatening beatings. Research on past child abuse reports in the United States indicates that about 25 to 35 percent of women and 10 to 20 percent of men, when asked, recall experiencing sexual abuse as children. Additionally, around 10 to 20 percent of both men and women report experiences that align with definitions of physical abuse.

Multiple studies indicate that 35 to 70 percent of female mental health patients acknowledge when asked, a childhood history of sexual abuse (Briere, 1992). Psychological abuse and neglect are also prevalent among children, although it’s more challenging to measure their occurrence in terms of incidence or prevalence (Briere, Godbout, & Runtz, 2012; Hart et al., 2011).

Child abuse and neglect not only result in significant and sometimes long-lasting post traumatic stress disorder but are also linked to a higher chance of experiencing sexual or physical assault later in life, often called revictimization (Classen, Palesh, & Aggarwal, 2005; Duckworth & Follette, 2011).

Child abuse and neglect are likely to be one of the most significant risk factors for later psychological difficulties among all traumatic events. This is because they happen early in life when the child’s neurobiology is particularly vulnerable, and enduring cognitive models about self, others, the world, and the future are being established.

Related Reading: How Childhood Trauma Affects Us

Mass Interpersonal Violence

Intentional violence that involves high numbers of injuries or casualties— but does not occur in the context of war—is a newer category in the complex trauma field. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, are a blatant case of mass acute trauma in Western society. There is an unfortunately large number of other examples, including terrorist attacks throughout the world and mass human rights abuses.

Natural Disasters

Natural disasters are broadly defined as large-scale, not directly human-caused, environmental events that result in injuries or deaths and negatively impact many people. In the United States, disasters are relatively common; surveys indicate that between 13 and 30 percent of individuals have experienced one or more natural disasters in their lifetimes (Briere & Elliott, 2000; Green & Solomon, 1995).

Common disasters encompass earthquakes, large fires, floods, tsunamis, avalanches, hurricanes, tornadoes, and volcanic eruptions. While some individuals exposed to disasters may initially be unaffected or recover swiftly, a substantial proportion experience significant post traumatic stress disorder (e.g., Briere & Elliott, 2000; Holgersen, Klöckner, Boe, Weisæth, & Holen, 2011).

The most distressing aspects of disasters seem to be the level of physical injury, the fear of death, the loss of loved ones, and property damage.

Large-Scale Transportation Accidents

Transportation accidents, like airplane crashes, train derailments, and maritime incidents (such as ship accidents), typically result in multiple victims and high fatality rates.

Determining the frequency of such traumatic events is challenging, but survivors of large-scale transportation accidents can find these experiences exceptionally terrifying. Such incidents often unfold over a relatively prolonged period, subjecting victims to ongoing terror and fear of death.

Fire and Burns

While the trauma literature commonly categorizes large-scale fires as disasters, many survivors seen by trauma clinicians have been harmed by smaller fires. These incidents involve house fires, often triggered by smoking in bed, electrical short circuits, or issues with propane tanks, stoves, or heaters.

Significant burns can occur due to car accidents, industrial fires, fireworks, barbecue mishaps, or intentional burning by others. Injuries from fire can be particularly traumatic.

The enduring physical consequences of severe burns, such as intense pain, an extended recovery period, numerous surgeries, the presence of visible and painful scars, disfigurement, amputation, and decreased mobility, mean that the traumatic event, in some aspects, persists and recurs over time (Gilboa, Friedman, Tsur, & Fauerbach, 1994). This often results in severe and chronic psychological trauma.

Motor Vehicle Accidents

Around 20 percent of individuals in the United States have been in a severe motor vehicle accident, and over half of American adults will experience a car accident by the age of 30 (Hickling, Blanchard, & Hickling, 2006). A significant number of these individuals may develop notable psychological symptoms, mainly if the accident caused substantial injuries or resulted in the death of others.

In such instances, grief and self-blame might intensify later psychological effects. Moreover, survivors of significant motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) may experience traumatic brain injury, adding complexity to both assessment and treatment.

Even though serious motor vehicle accidents are more likely than other types of trauma to result in post traumatic stress disorder and other forms of dysfunction, clinicians frequently neglect to appropriately inquire about such traumatic events when discussing adverse life events with clients.

Rape and Sexual Assault

Rape is the nonconsensual penetration of an adolescent or adult’s mouth, anus, or vagina involving a body part or object, often through threats, physical force, or when the victim is unable to give consent due to drugs, alcohol, or cognitive impairment. Sexual assault refers to coerced sexual contact, including rape. (For child victims, refer to here, for more information).

The prevalence of rape against women in the United States ranges from 14 to 20 percent. Peer sexual assault against adolescent women is prevalent, with 12 to 17 percent coerced into sexual acts against their wishes. Around 12 to 13 percent of female adolescents in America have encountered sexual assault or rape.

Sexual assault rates for males range between 2 and 5 percent, including military sexual trauma (MST). Studies show 15 percent of women and 1 percent of men in the military experienced MST while on active duty. In refugee situations or war-torn countries, women frequently undergo rape, often used as a tool of violence by invading forces. Additionally, women and children experience rape or sexual assault during illegal immigration, such as by human traffickers smuggling them across borders.

Stranger Physical Assault

Stranger physical assault involves attacks like muggings, beatings, stabbings, shootings, attempted strangulations, and other violent actions against someone not familiar to the assailant. The motivation for such aggression is frequently robbery or the expression of anger. In gang and “drive-by” situations, the intent may also be to establish or protect territory or to assert dominance in other ways.

While many acts of violence in relationships are more often directed towards women than men, the opposite seems to be the case for stranger physical assaults (Amstadter et al., 2011). In a study of urban psychiatric emergency room patients, for instance, 64 percent of men reported experiencing at least one non intimate physical assault, compared to 14 percent of women (Currier & Briere, 2000).

Likewise, Currier (2000) discovered that, depending on the research site, 3 to 33 percent of male adolescents reported a traumatic event such as being shot at or shot, and 6 to 16 percent mentioned experiencing attacks or stabbings with a knife.

Intimate Partner Violence

Commonly referred to as wife battering, spousal abuse, or domestic violence, intimate partner violence is typically defined as physically or sexually assaultive behavior by one adult against another in a personal and often cohabiting relationship (learn about the perils of cohabitation).

In the vast majority of instances, emotional trauma is also present, encompassing humiliation, degradation, severe criticism, stalking, or threats of violence against children, pets, and property (Kendall-Tackett, 2009).

In a broad survey of individuals in the United States who were married or living with a partner, 25 percent reported at least one traumatic event involving physical aggression in a domestic setting, and 12 percent reported incidents of severe physical violence like punching, kicking, or choking (Straus & Gelles, 1990).

Likewise, findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey indicate that 20 percent of women in the general population have experienced physical assault by their current or former partner, compared to 7 percent of men (Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000).

As per the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control’s National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (Black et al., 2010), when considering all forms of intimate violence together, 36 percent of women and 28 percent of men in the United States have encountered rape, physical violence, and stalking by an intimate partner.

The occurrence of domestic violence among women with mental health disorders or seeking services from a mental health professional is even higher, occasionally surpassing 50 percent (for instance, Chang et al., 2011). As anticipated, the consequences of such violence are substantial, affecting both medical and psychological aspects.

Sex Trafficking

Sex trafficking is the compelled or coerced recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring, or receipt of individuals for commercial sexual exploitation.

While precise figures are challenging to ascertain, it is estimated that 600,000 to 800,000 individuals are trafficked for sex or forced labor across international borders each year, with 14,500 to 17,500 trafficked into the United States (U.S. Department of State, 2005).

Once trafficked, women, girls, and less frequently, boys are compelled into various activities, including prostitution (in brothels and on the streets), pornography, strip shows, massage parlors, escort services, mail-order bride networks, and sex tourism.

One can argue that local prostitution, when coerced or compelled by a pimp or brothel, is also a form of sex trafficking, albeit one that does not involve physical relocation.

The consequences of sex trafficking are frequently severe (encompassing both physical and psychological trauma). Participation in prostitution, along with the accompanying effects of the trafficking process (such as being kidnapped or coerced into slavery, experiencing rape and beatings as punishment for noncompliance, and being illegally transported to another country without documents, where a different language may be spoken and isolation is severe), has been linked to high rates of depression, mental and physical health complications, substance abuse, and other symptoms and disorders.

Torture

The United Nations Convention Against Torture defines torture as intentionally causing severe physical or mental pain or suffering to a person for purposes such as extracting information, getting a confession, punishing for a committed or suspected act, or intimidating the person or others.

In the current U.S. Code (Title 18, Part I, Chapter 113C, Section 2340), torture is described as an act committed by someone in an official capacity, aiming to intentionally inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering on a person under their control, excluding pain or suffering related to lawful sanctions.

Regardless of the situation, torture methods involve both physical and psychological techniques. These include beatings, almost strangling someone, using electrical shocks, various forms of sexual assault and rape, breaking bones and joints, waterboarding, sensory deprivation, threats of death or mutilation, fake executions, making someone feel responsible for harming others, depriving them of sleep, exposing them to extreme cold or heat, forcing stress positions, mutilation, and compelling individuals to participate in degrading or humiliating acts (Hooberman et al., 2007; Punamäki et al., 2010; Wilson & Droždek, 2004).

Around half a million torture survivors from Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Southeast Asia are believed to be living in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). However, these individuals are seldom asked about any history of torture when they interact with mental health systems in North America.

How Does Trauma Effect Our Mental Health?

Complex trauma refers to the experience of multiple, chronic, or prolonged traumatic events, often beginning in childhood and continuing into adulthood. Unlike single-incident trauma, complex trauma involves repeated exposure to distressing events, which can have a profound impact on an individual’s mental health.

The effects of complex trauma on mental health can be extensive and multifaceted. Individuals who have experienced complex trauma are at a higher risk of developing mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety. Emotional dysregulation, or difficulty managing emotions, is a common consequence, leading to frequent mood swings, intense emotions, and difficulty calming down.

Complex trauma can also impact an individual’s ability to form and maintain healthy relationships. Trust issues, fear of abandonment, and difficulties with intimacy are common challenges. These individuals may struggle with feelings of worthlessness and have a fragmented sense of self, making it hard to establish a stable and positive self-image.

What Are Treatments for Trauma?

There are several effective treatments available for trauma, each aimed at helping individuals process their experiences and manage their symptoms. These treatments include therapy, medications, and self-care techniques, all of which can play a crucial role in recovery.

Therapy

Therapy is often the first line of treatment for trauma. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy are two widely used approaches that have proven effective in treating trauma. CBT helps individuals identify and change negative thought patterns and behaviors, while psychodynamic therapy focuses on exploring past experiences and their impact on current behavior.

Related Reading: What Is Therapy Is It Effective?

Medications

Medications, such as antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications, can also be used to manage symptoms of trauma. These medications can help alleviate symptoms like anxiety, depression, and insomnia, making it easier for individuals to engage in therapy and other forms of treatment. However, medications should always be used under the guidance of a mental health professional to ensure they are appropriate and effective for the individual’s specific needs.

Conclusion

Understanding the causes and symptoms of trauma, recognizing the impact of complex trauma on mental health, and seeking appropriate treatments are essential steps in the journey toward healing and recovery. With the right support and interventions, individuals can overcome the effects of trauma and lead fulfilling lives.