The brain, the most complex organ in the body, influences everything we feel and do. It’s not just about our thoughts; our emotions and actions are deeply intertwined with brain function. Comprised of various structures, each serving a unique purpose, our brain relies on the seamless coordination of multiple areas to perform everyday tasks.

For instance, when we misplace our car keys, we instinctively try to visualize the last place we saw them and mentally retrace our steps. This seemingly simple process involves the coordination of different brain regions: the area responsible for storing visual memories and the one managing working memory.

Working memory helps us retrieve past information, compare it to current data, and devise a plan to solve the problem. We depend on our brain for these routine tasks daily, often without truly understanding the underlying mechanisms.

When it comes to trauma, once perceived as rare, we now recognize that traumatic experiences are alarmingly common, affecting millions each year. Trauma can stem from prolonged exposure to a distressing environment, such as child abuse, domestic violence, or war, or from a single catastrophic event like a terrorist attack or car accident. Trauma affects blood flow to different brain regions, impacting emotional regulation and responses to perceived danger.

Related Reading: Click Here To Learn More About The Different Types Of Trauma

Everyone is susceptible to trauma or affected by the trauma experienced by loved ones. Many don’t realize that the impact of a traumatic event extends far beyond the event itself, lingering in ways that continue to affect our lives even after the immediate danger has passed.

Understanding that trauma changes our normal brain development—allows us to begin healing. Traumatic experiences also impact brain chemistry, altering it as a protective mechanism. By delving into the mechanisms of the traumatized developing brain, we can better appreciate the profound ways in which trauma influences behavior, emotions, and overall mental health.

Understanding the Traumatized Brain

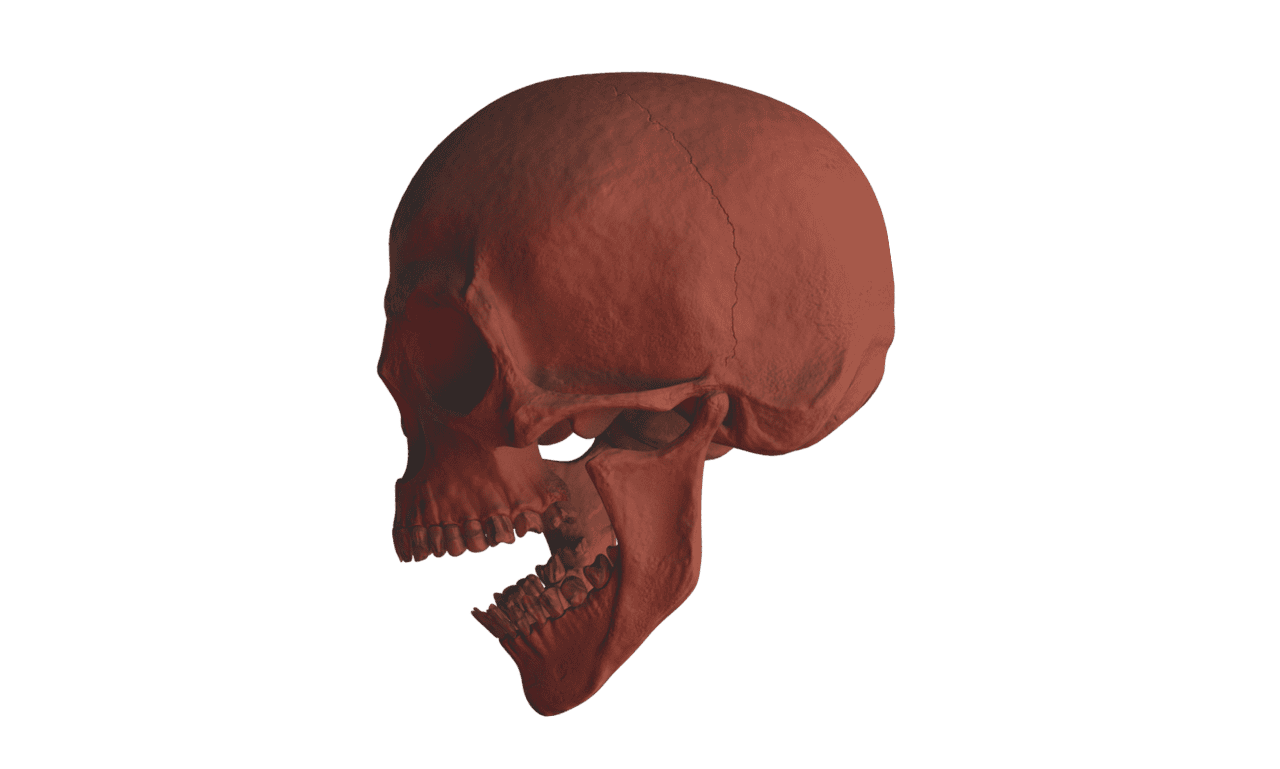

The brain model most often used in trauma treatment is the triune brain, developed by neuroscientist Paul MacLean in 1967. While modern science has advanced beyond this model, it remains useful for trauma survivors and their therapists because it simplifies the brain into three distinct areas, making it easy to remember and apply. MacLean divided the brain into three regions: the prefrontal cortex (or thinking brain), the mammalian brain, and the reptilian brain. The brain stem, located below the limbic system, plays a crucial role in the neurobiological response to trauma by initiating physiological responses to stress.

What is the reptilian brain responsible for?

The reptilian brain is crucial for survival, controlling basic functions like heart rate, breathing, reflexes, and instinctive responses. Picture a lizard: it doesn’t stop to think; it reacts quickly, automatically, and instinctively.

Newborn babies are born with a fairly well-developed reptilian brain and only the beginnings of a mammalian brain and a thinking brain. Their initial life challenges involve breathing, heart rate regulation, digestion, and nervous system regulation. Parents might say, “My baby just sleeps, cries, eats, and poops,” not realizing this indicates the reptilian brain is diligently working to ensure their baby’s survival.

What is the mammalian brain responsible for?

Around three months of age, most babies become more social. They smile when they see a beloved figure, wiggle and squeal with excitement, and make little faces and sounds. These smiles are often so contagious that even weary, sleep-deprived parents cannot help but smile back. This milestone signifies the rapid growth of the limbic system, or mammalian brain, which lays the foundation for the baby’s future emotional and social development.

The emotional reactivity of small children highlights the dominance of the limbic system during early childhood. Their ability to be rational and organized in their behavioral responses develops slowly as the thinking brain, or prefrontal cortex, matures throughout the childhood years. Trauma can lead to negative emotions, making it challenging for children to manage these feelings effectively.

What is the thinking brain responsible for?

By 11 or 12 years of age, most children can use reason instead of emotion to communicate their needs. However, the prefrontal cortex is still not fully developed. It is estimated that the prefrontal cortex continues to grow and become more refined until around the age of 25—well past adolescence.

This extended development period helps explain why adolescents often don’t mature until their early 20s. Their brains simply do not support full maturation until the prefrontal cortex has completed its growth and subsequent reorganization process.

If you sometimes feel shame or guilt over how you acted as an adolescent, remember that your brain was still developing. The rapid growth of the brain at ages 12 to 13 disrupts its maturation.

During this time, children experience intense feelings and impulses. Their prefrontal cortex suddenly grows but remains disorganized and immature. As a result, adolescents often make decisions based on impulse or emotion rather than reason, simply because their brains have not yet caught up.

How does the brain respond to trauma?

Both single traumatic events and enduring traumatic conditions profoundly affect the developing brains of children (Perry et al., 1995). Childhood abuse (of any kind) leads to chronic stress or overstimulation of the reptilian and mammalian brains, while simultaneously shutting down the prefrontal cortex. These changes are not due to any physical injury but rather the brain’s response to trauma. Consequently, certain mental processes, such as learning, become more challenging for traumatized individuals.

In children, this overstimulation can manifest as heightened impulsivity and reactivity, potentially resulting in diagnoses of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Oppositional Defiant Disorder or other anxiety disorders. Alternatively, the child may appear unmotivated. In abusive environments, constant stimulation by threats or reminders of past trauma prevents the lower brain regions from supporting the maturation of the prefrontal cortex.

Neuroscience research indicates that trauma-related emotional and body memories are stored in the amygdala and can be easily triggered by reminders of traumatic events or by recalling them. Furthermore, verbal memory areas, responsible for coherent storytelling, shut down when the amygdala is triggered and reactive. Consequently, after a traumatic event or a traumatic life, survivors might have only a fragmented narrative of what happened, or no clear story at all.

Many survivors report, “I don’t remember anything,” without realizing that they are indeed remembering when they suddenly startle, feel afraid, tighten up, pull back, feel shame or self-hatred, or start to tremble. Because trauma is primarily remembered emotionally and somatically rather than in a narrative form, survivors often feel confused, overwhelmed, or disoriented. Without memories expressed in words or pictures, they may not recognize their feelings as memories at all.

Related Reading: Unsure If You Have Trauma? Find Out Now

Is our memory altered after trauma?

Human beings do not just remember events; we remember in various ways. Each brain area stores memory differently. With the thinking brain, we might recall the story of what happened without much emotion attached to it. Our sensory systems might spontaneously evoke images or sounds connected to the event. Emotion can trigger memories of how something felt, while our bodies remember impulses, movements, and physical sensations experienced at the time (such as tightening, trembling, sinking feelings, fluttering, or quivering).

Despite experiencing these different ways of remembering, many people are unaware of them, even though they are all too familiar with suddenly feeling anxious or angry for no apparent reason. When triggered, they may not recognize that what they are experiencing is a memory.

For example, they might feel warmth when thinking about loved ones or experience a sense of pulling back or bracing when encountering someone threatening. Déjà vu experiences—feeling like ”I’ve been here before” or that something seems familiar without knowing why—are also forms of memory without words.

For trauma survivors, understanding these non-verbal forms of memory can be crucial. Trauma affects brain development and memory, leading to long-lasting impacts on emotional and mental wellbeing. If a feeling or reaction is painful, confusing, or overwhelming, it is likely a feeling or body memory. Many survivors feel uncomfortable when they don’t remember entire events or when memories are fragmented or unclear. They may doubt themselves, thinking they must be making things up if they can’t remember clearly.

It’s essential to recognize that trauma cannot be remembered in the same way as other events due to its effects on the brain. When you feel the impulse to doubt your memory or intuition about something that happened, remind yourself that recalling events as a story or narrative isn’t the only way of remembering. You may be remembering more than you think!